Product Portfolio Optimization

2009, 2010, 2011… 2020… Each year, like clockwork, the same questions from senior executives and the company board have come back, haunting me about product portfolio management. Albeit, very polite yet probing questions, challenging me in my journey as a General Manager:

“How come you keep building products in that category? For what reasons are you doubling down investment on that product line? Why don’t you EOL that under-performing offering?”

Sounds familiar? You’re in good company! Every business ends up facing the question of how to make sure we’re betting on the right horses.

Over time, sophisticated tools have emerged to help you manage your product portfolio. That’s all very fine, but how do you choose what’s right for your business? How not to oversimplify and risk losing sight of what matters for your company? As importantly, how to avoid losing time and energy for the sake of proper strategic thinking?

These are critical questions, so let’s debunk a few myths about product portfolio management and let me share the four principles that helped me focus on what mattered.

Definition, History and Tools Inventory

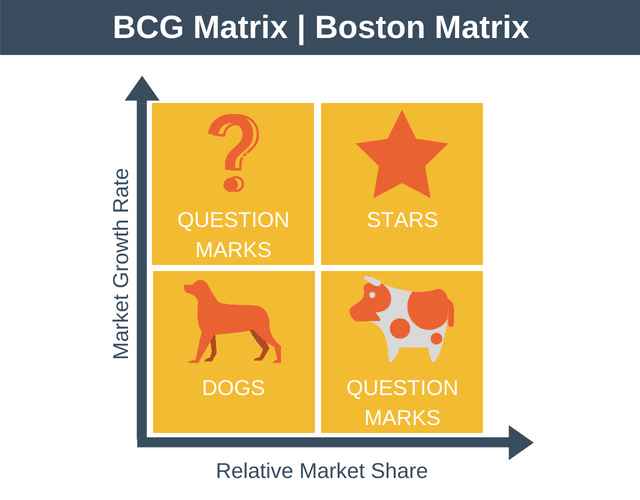

Product Portfolio Management emerged in the seventies as the BCG (Boston Consulting Group) made its Growth-Share 2×2 matrix notorious. In a nutshell, it is about evaluating your products’ performance with risks and opportunities, mapping to your strategic imperatives. Do it right, and chances are you will experience growth and profit.

Such analysis provides a simplified model with four buckets. The two variables are how attractive your category is (growth rate) and your competitive position (relative market share). You end up with “Stars” (all good!), “Dogs” (Problem Children), “Cash Cows” (paying for the bills), or “Question Marks” (future bets). At a minimum, it can help fuel the right conversations in the board room. But how reliable is that matrix? Are the market share and growth rate proper proxies?

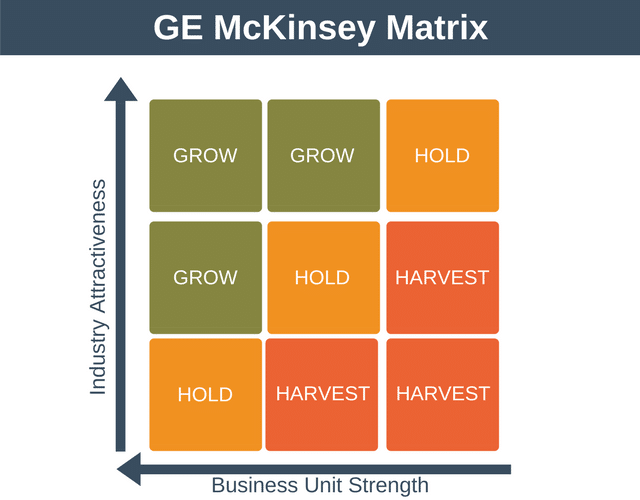

An evolution of the BCG Matrix provides a view on how attractive a category or industry is and how strong your different business units are (GE and Mc Kinsey 3×3 matrix). It goes farther, but it also falls short if you struggle with the relative nature of the attributes: “What makes a category attractive? How do we assess our business strengths?”.

With these issues in mind, others have turned to a more composite approach. The outcome can still be a “simplified” matrix. Yet, the set of criteria used for the analysis goes beyond two simple dimensions. For instance, you determine the attractiveness of a category with growth rates, competitive investment levels, disruption risks, macro trends. Very quickly, though, you start wondering if you’re not over-analyzing it!

So how can you do it the right way? You could spend a lot of time considering which tools and techniques are best suited for your situation. Having been through the exercise every year in the past decade, it helped me establish some foundation first. Let me now share the four principles that saved me more than once!

Principle #1 - Sort out your WHY

Being clear about WHY your company is in business is paramount. I recently wrote a post on that specific topic: “Sort out the WHY or fail!“. By focusing on the authentic values that bring you and your colleagues to work, day after day, you can articulate your WHY and related strategic objectives. Then, keep it as a filter for every single thing you do. It can be as easy as asking yourself: “Knowing our strategic objectives, how does this product family align?”

Principle #2 - Identify your unique criteria

There’s not a single universal metric for success. Profitable growth might be a great reference. But, your past performance is not a guarantee of future success. Find proxies that match your situation. In my experience, I noticed that rather than looking into market share, analyzing profit share was more relevant. Also, how do you consider potential disruptors in your market, any technology shift that enables new applications, or any macro phenomenon like COVID-19? Every company has a unique set of evolving criteria, so you should play with these before settling on the ones that truly matter.

Principle #3 - Involve the right stakeholders

Every organization is unique, made of talent and personalities with different sensitivities. One lesson I learned is that product, and business leaders are better off if they’re more inclusive than not. It doesn’t mean leading by committee. Just make sure you appropriately involve the board, key executives, business unit, and the critical partner functions. You will save a lot of cycles if you’re clear on who should define these with you, and who should be consulted or just informed.

Principle #4 - Dare to act and execute

How often have I seen the following outcome of the analysis: “We should have divested this product line but, we ended up sticking to it for another set of years. We seriously jeopardized our chances of investing in more strategically aligned categories and kept distracting our operations with underperforming and futureless products”. If your portfolio analysis concludes that a product line (or product) is a “Dog,” then act on it and establish a clear divest plan with all your key stakeholders (including your Sales Team!) and execute.

In conclusion, no matter what size your business is or how many products you carry, you’d better establish the world-class practice of proactively managing your product portfolio. It is essential to proper strategic planning and acts as a foundation for your operating plan. The four principles I highlighted should help with that framework!

I’m genuinely interested in getting your feedback on this topic! How successful have you been in optimizing your own product portfolio? Which other considerations worked for you? Just comment on this blog or drop me a note on The Product Sherpa site!

And, if you want to optimize your own strategy and maximize profit, The Product Sherpa is here to help you. We offer custom makeover programs for tangible results in just a few weeks. You can drop us a note, or schedule a free exploratory call.